PDA Stress Response Strategies

PDA and Stress-Response Support Strategies

As a PDA Autistic adult and parent to two PDA Autistic children, I understand the complexities of navigating a demand-filled world. This post will explore PDA stress-response support strategies, including how to recognise burnout, recovery, and regulation cycles, and practical ways to support autonomy while reducing distress.

Understanding PDA and the Stress-Response System

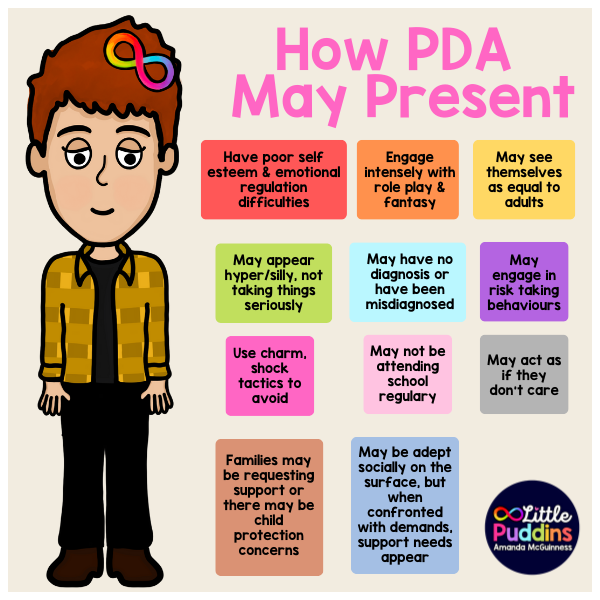

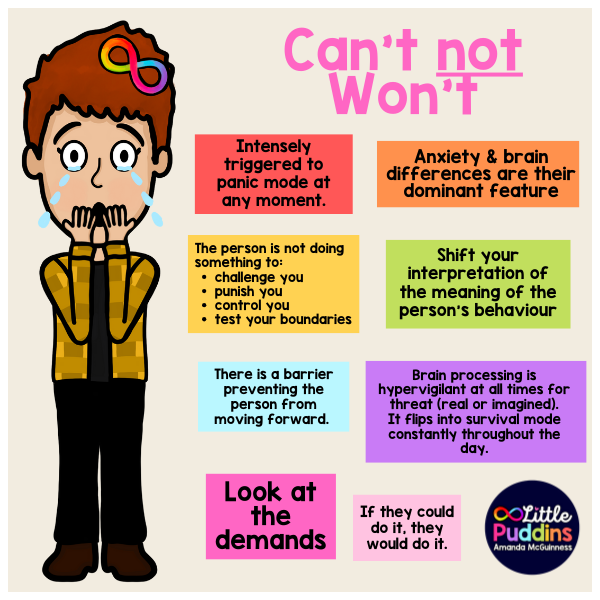

The PDA Society UK identifies the PDA profile as characterised by an intense need for autonomy, which can affect self-regulation and engagement with external expectations. PDA is not a defiant behavioural choice, but a response to demands that can trigger self-protective coping mechanisms such as:

Heightened sensitivity to control: Requests may feel overwhelming or intrusive.

Autonomy as a self-regulation strategy: Maintaining control is essential for emotional stability.

Cumulative stress overload: Unaccommodated demands lead to withdrawal and burnout.

Fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses: Coping mechanisms triggered by perceived demands.

These responses are not defiance or manipulation, but instinctive reactions requiring adjustments in approach to ensure psychological felt safety.

This response is linked to heightened sensitivity to perceived control, where external expectations can be interpreted as intrusive or unmanageable. Understanding PDA through a biopsychosocial lens allows for the implementation of effective accommodations, fostering trust, reducing distress, and supporting well-being.

The Burnout-Recovery-Regulation Cycle in PDA

Recognising the phases of PDA stress regulation allows for tailored interventions. The three primary phases include:

1. Burnout (Chronic Stress Exhaustion)

Caused by ongoing exposure to unaccommodated demands.

Signs include withdrawal, distress, and disengagement from self-care.

Requires immediate reductions in expectations and predictable environments.

2. Recovery (Restorative Autonomy & Adjustments)

Reducing demands and adjusting environments restores emotional stability.

Co-regulation with a trusted person fosters psychological safety.

3. Regulation (Sustainable Equilibrium & Interaction Tolerance)

Gradual increase in engagement with structured autonomy.

The goal is to prevent distress escalation while affirming self-directed autonomy.

PDA Stress-Response Support Strategies

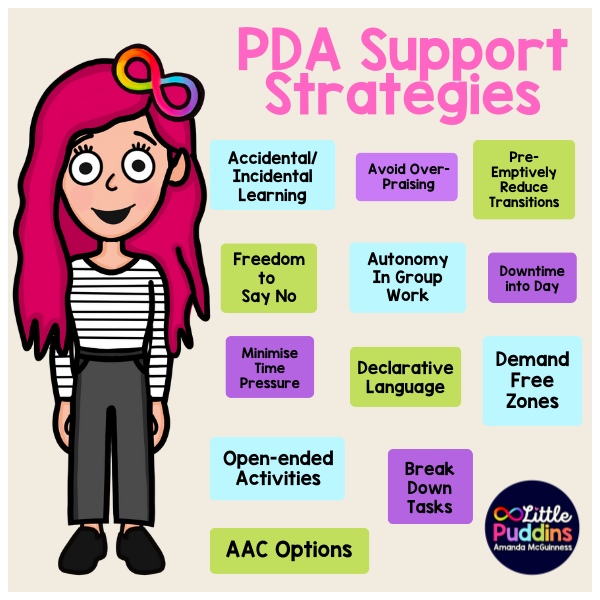

1. Prioritise Emotional Regulation Over Compliance

Traditional behaviour models (e.g., reward charts) can heighten distress (PDA Society UK, 2023).

Instead, relationship-first approaches (trust-building, co-regulation) promote long-term engagement

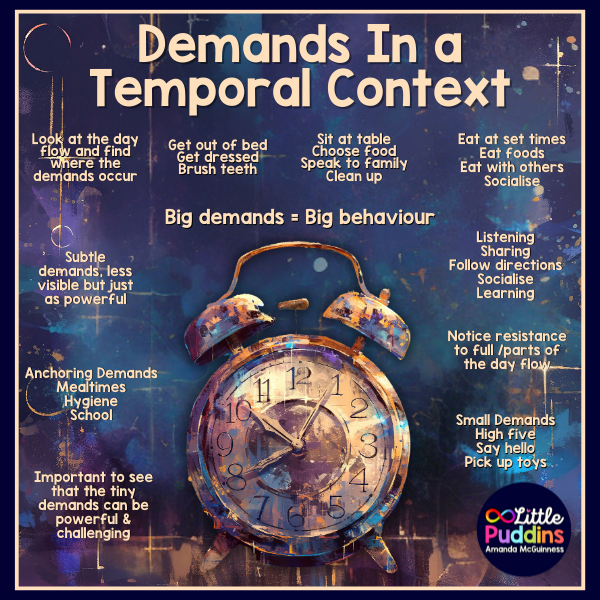

2. Reduce Both Explicit and Implicit Demands

Minimise perceived control through non-directive communication and declarative language.

3.Encourage Autonomy Within Predictable Structures

Offer flexible choices within safe frameworks (e.g., “Would you like to wear boots or trainers?”).

4.Reframe “Clinginess” as a Self-Regulation Need

Many PDA children require continuous engagement with a trusted person for stability.

Gradually scaffold transitions instead of pushing for independent separation.

5.Monitor Daily Fluctuations in Stress Regulation

Demand tolerance varies daily—adapt expectations in real-time to prevent burnout.

6.Use Co-Regulation Instead of Correction

Dysregulation is best met with calm, non-directive support rather than discipline or correction.

7.Replace Fixed Rules with Adaptive Boundaries

Rigid rules can increase distress, while contextual boundaries allow for moment-to-moment flexibility.

PDA Parenting & Caregiver Checklist

Prioritise emotional regulation before instruction.

Establish felt safety before setting expectations.

Recognise autonomy as a core self-regulation need.

Identify early signs of burnout before escalation.

Use de-escalation over traditional discipline models.

Monitor your own emotional regulation as a caregiver.

Get in Touch: Contact Amanda

Follow for Insights: Instagram @littlepuddins.ie

References:

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) and the Nervous System:

1. Foundational Understanding of PDA:

Newson, E., Le Maréchal, K. and David, C. (2003) ‘Pathological demand avoidance syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(7), pp. 595–600. Available at: https://adc.bmj.com/content/88/7/595 (Accessed: 1 February 2025).

Johnson, M. and Saunderson, H. (2023) ‘Examining the relationship between anxiety and pathological demand avoidance in adults: A mixed methods approach’, Frontiers in Education, 8, Article 1179015. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1179015/full (Accessed: 2 February 2025).

O’Nions, E., Happé, F., Viding, E. and Noens, I. (2021) ‘Extreme demand avoidance in children with autism spectrum disorder: Refinement of a caregiver-report measure’, Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 5(3), pp. 1–13. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41252-021-00203-z (Accessed: 1 February 2025).

O’Nions, E., Christie, P., Gould, J., Viding, E. and Happé, F. (2014) ‘Development of the “Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire” (EDA-Q): Preliminary observations on a trait measure for pathological demand avoidance’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(7), pp. 758–768. Available at: https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpp.12149 (Accessed: 2 February 2025).

2. Neurophysiological Perspectives:

Porges, S.W. (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S.W. (2001) ‘The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system’, International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42(2), pp. 123–146.

3. Insights for PDA Practitioners:

O’Nions, E., Happé, F., Viding, E. and Noens, I. (2021) ‘Extreme demand avoidance in children with autism spectrum disorder: Refinement of a caregiver-report measure’, Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 5(3), pp. 1–13. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41252-021-00203-z (Accessed: 1 February 2025)

Haire, L., Symonds, J., Senior, J. and D’Urso, G. (2024) ‘Methods of studying pathological demand avoidance in children and adolescents: A scoping review’, Frontiers in Education, 9, Article 1230011. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1230011/full (Accessed: 1 February 2025).

4. Neuroscience and Trauma-Informed Perspectives:

Porges, S.W. (2009) ‘Reciprocal influences between body and brain in the perception and expression of affect: A polyvagal perspective’, The Healing Power of Emotion: Affective Neuroscience, Development & Clinical Practice, pp. 27–54.

5. Real-World Lived Experience and Clinical Application:

Christie, P. (2018) ‘PDA… the story so far’, PDA Society Resources. Available at: https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/resources/phil-christie-pda-the-story-so-far/ (Accessed: 1 February 2025).